SpLyCI - Integrating Spreadsheets by Recognising and Solving Layout Constraints

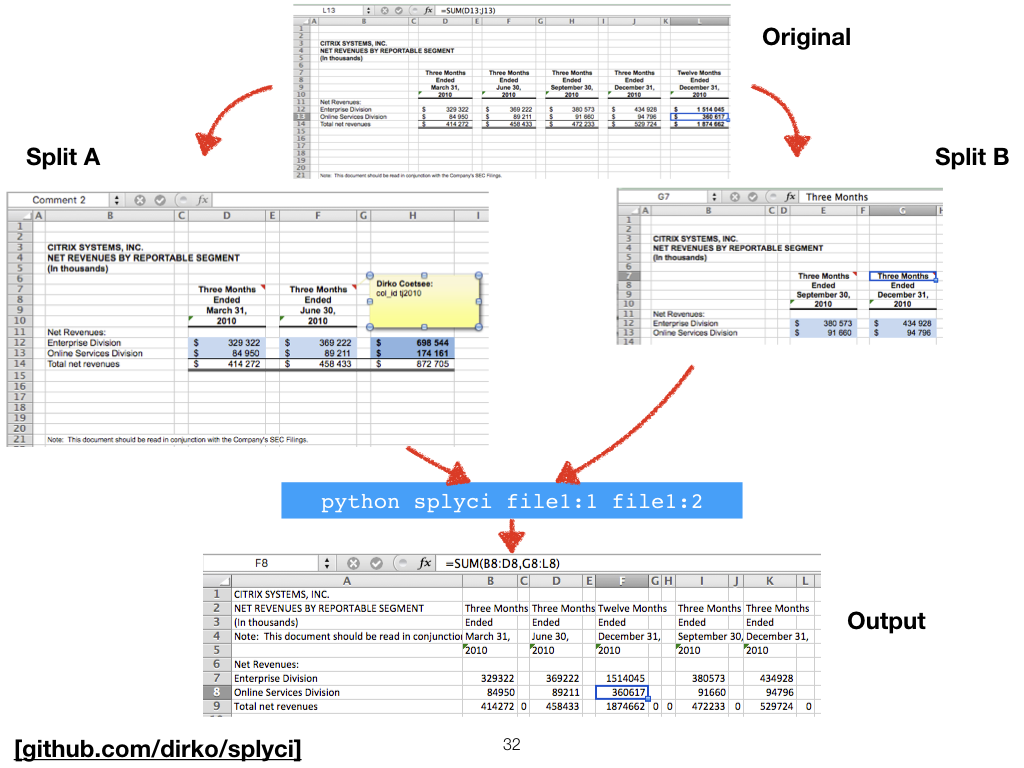

I presented a paper at IDA 2021 entitled: SpLyCI: Integrating Spreadsheets by Recognising and Solving Layout Constraints. This post (adapted from the talk) explains how to merge two spreadsheets (semi-)automatically. The code is available as a python package at github.com/dirko/splyci.

Motivation

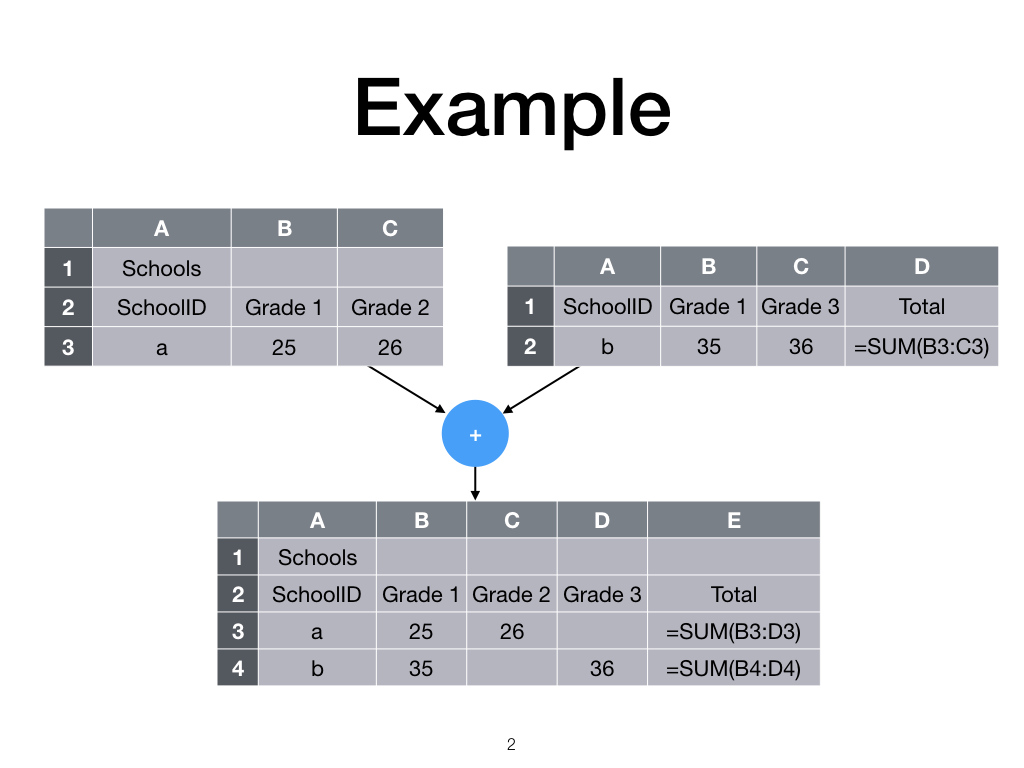

Semi-structured data sources often contain information that would be useful if they could be converted into the right format. Spreadsheets, in particular, often have their data spread over different sheets or even files, each corresponding to a different data source or some other partitioning of the data. To work with such spreadsheets can take considerable effort, as there is not yet any tool to help consolidate data into a single sheet before further analysis can be done. As part of a larger project to make data science more accessible to spreadsheet users, we aim to create a tool that can semi-automatically merge multiple spreadsheets, while handling repeated formulae correctly. A user specifies mul- tiple input sheets and the tool (semi-)automatically transforms the input sheets into a single output sheet

Previous approach

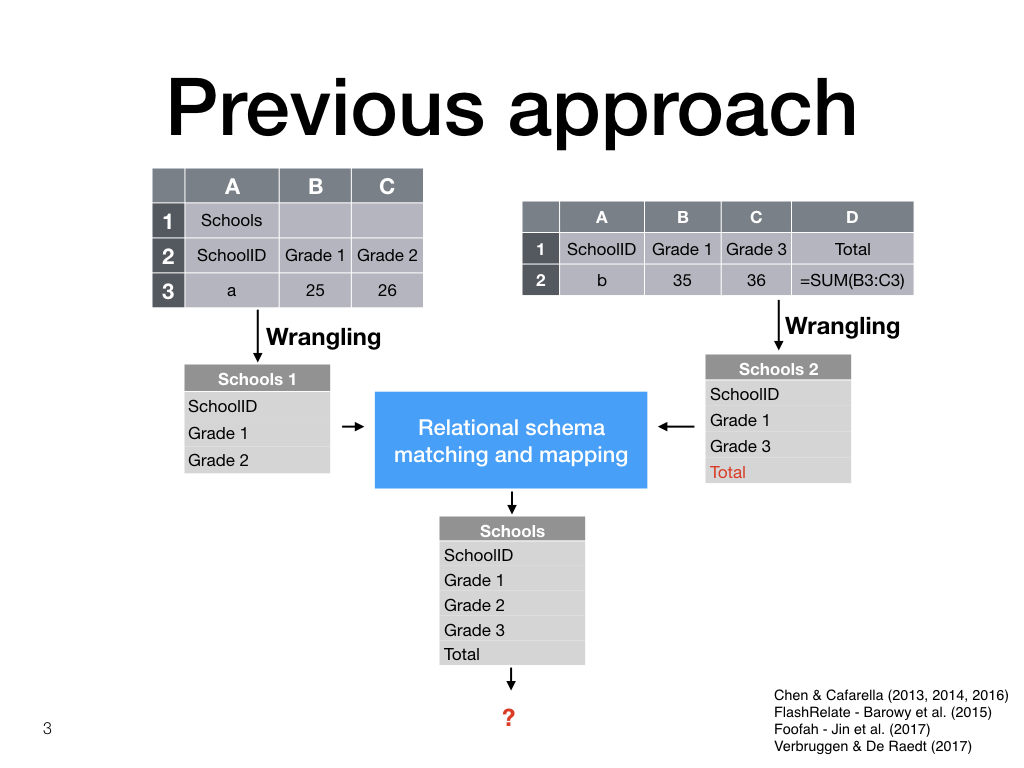

Previous approaches to Spreadsheet Integration first transform the input spreadsheets to a relational format, before applying relational matching and mapping techniques.

These approaches do not lay out the result again as a spreadsheet, and do not take formulae into account.

Our approach

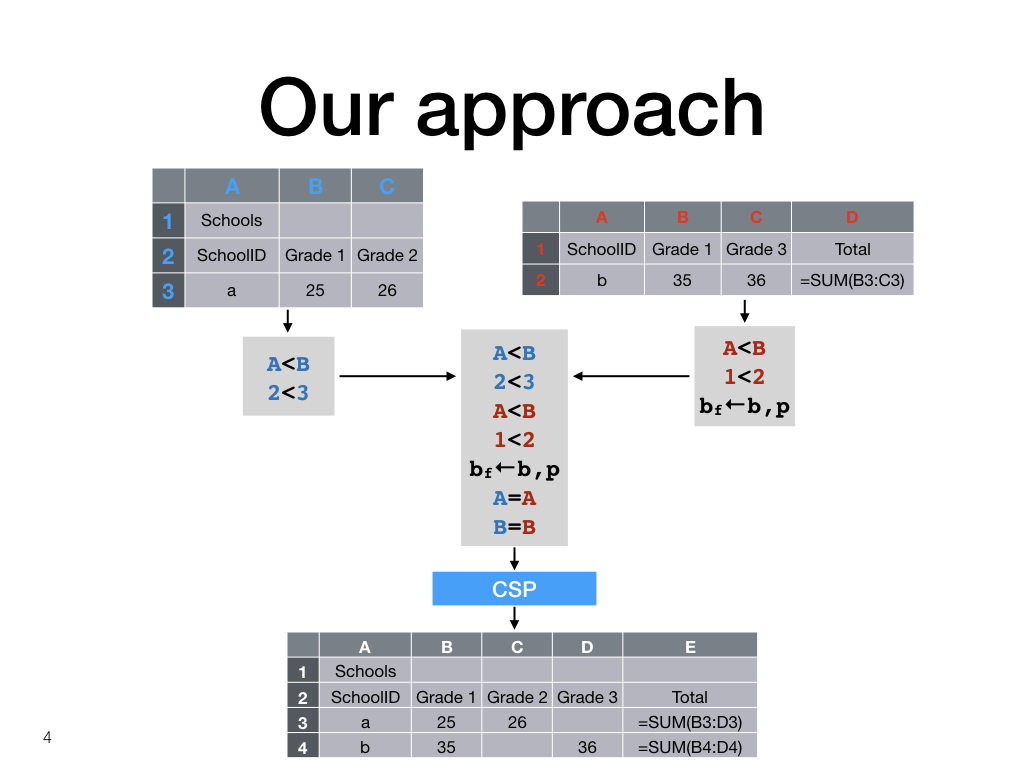

In contrast, our approach recognises implicit layout constraints, combines them, and solves the resulting constraint satisfaction problem to again produce a spreadsheet.

Outline

By the end of this post I will have shown you how this technique works by working through an example, first for spreadsheets without formulae, and then for the more interesting case with formulae.

Then, I will present experimental results and conclusions.

Example cut

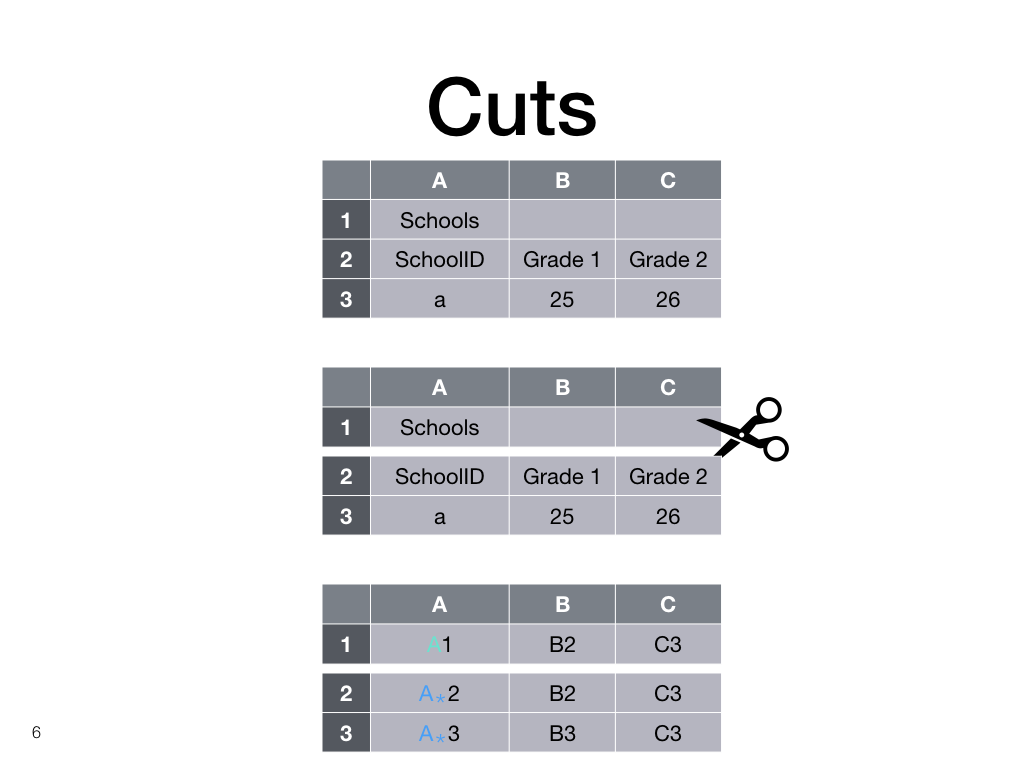

Let’s look at the example again. The descriptive first row does not really have to line up perfectly with the rest, and we represent this knowledge by making a distinction between the A column and the A-star column.

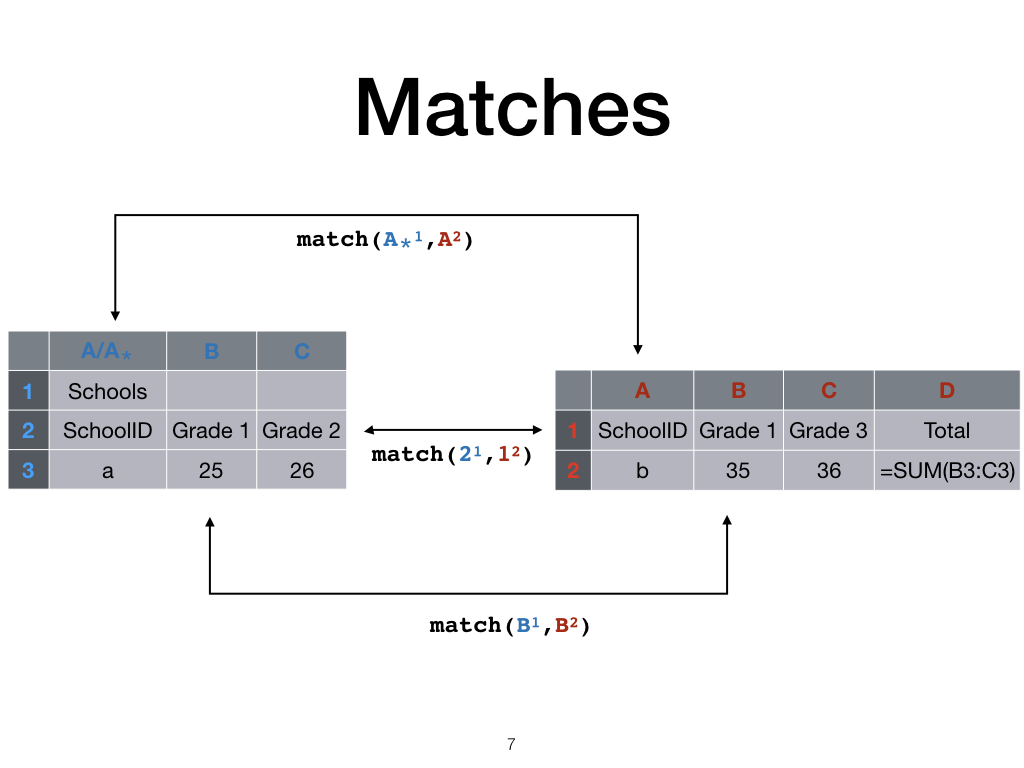

Matches

Now that every column and row is uniquely identified, we can represent matches between different sheets with the match predicate. In this paper we assume that columns or rows match when their first cells match.

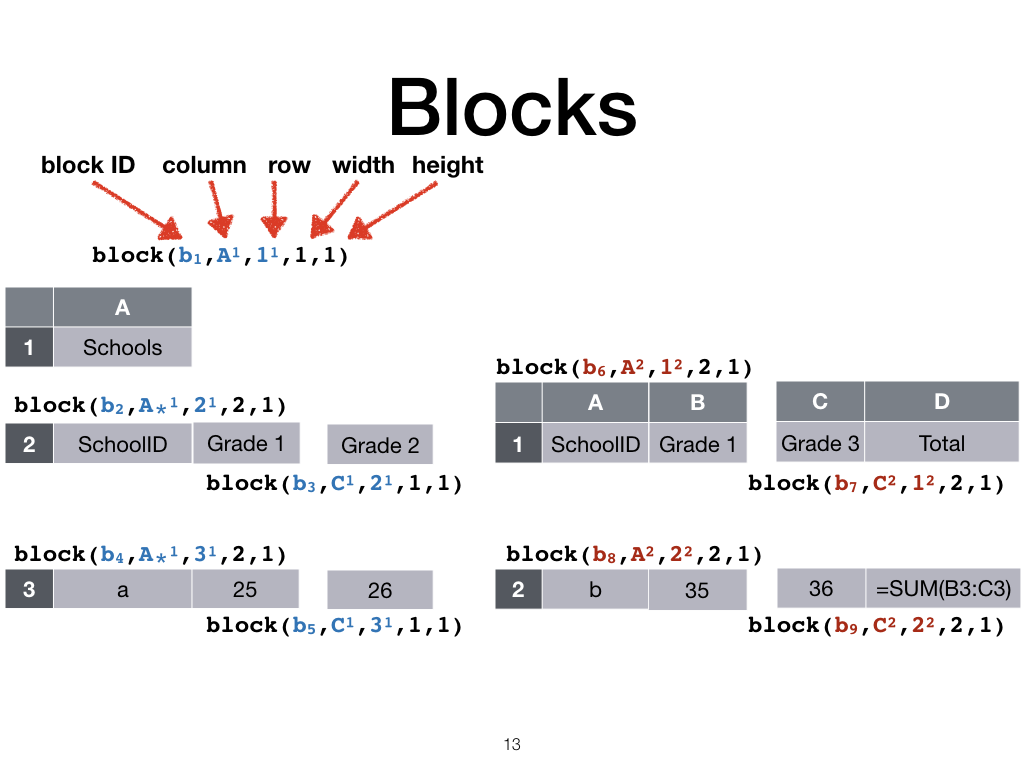

Blocks

For efficiency in large spreadsheets, we work at a block level and not the cell level. We want the same properties for blocks as what would have been the case for cells, so we split the spreadsheet into blocks using a few rules.

Firstly, a cut partitions the sheet into blocks.

Secondly we partition the sheet if only one of two neighbouring rows or column match.

Now we end up with blocks that are represented with the block predicate.

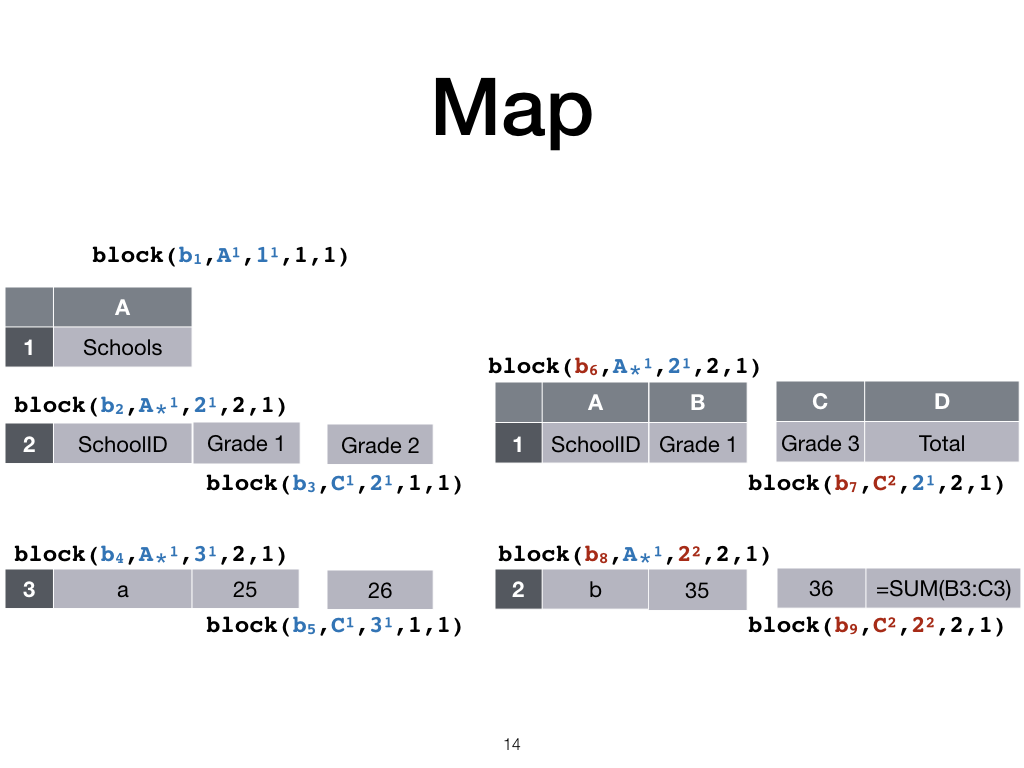

Map

Now we map columns and rows from both sheets to a common set of columns and rows, in this case the left-most sheet’s.

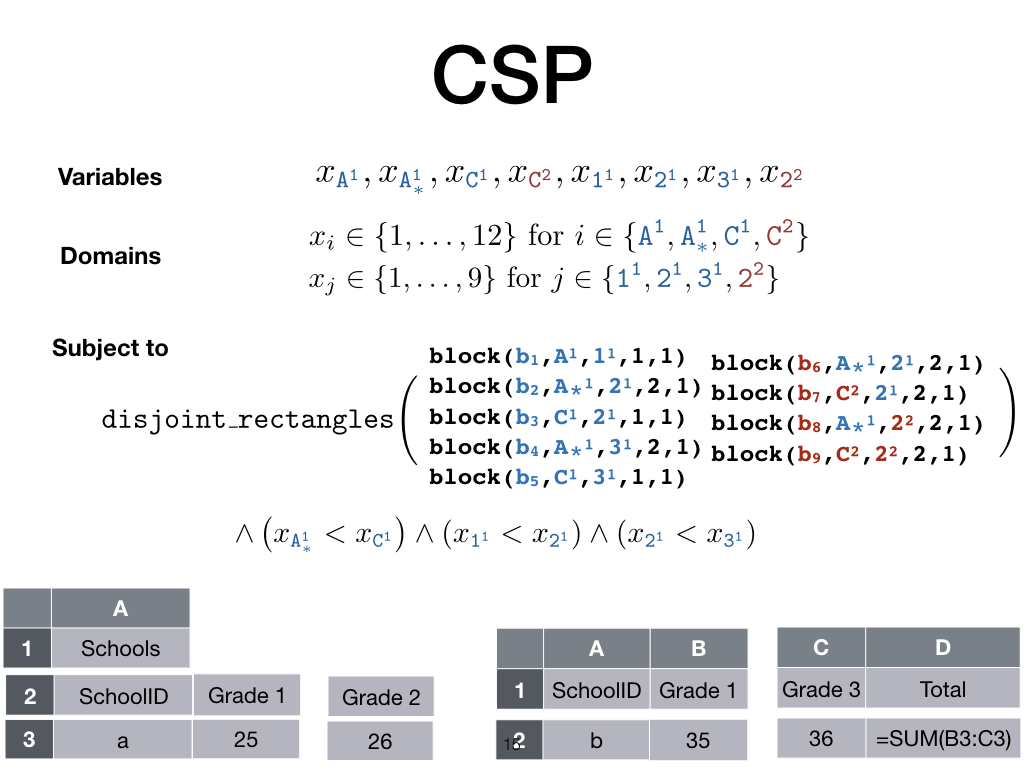

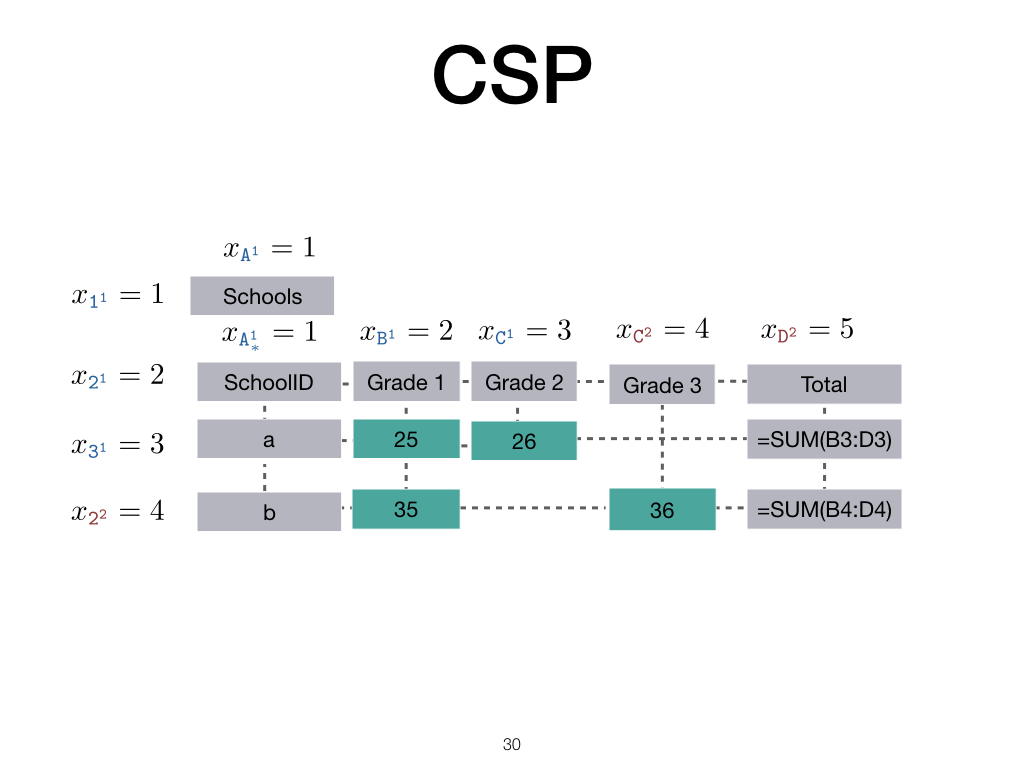

CSP

And lastly the knowledge about blocks and their relative positions are encoded as a constraint satisfaction problem.

Each row or column is assigned a new value such that the blocks do not overlap, and the relative order between columns and rows is preserved. For example, column A-star should be to the left of column C.

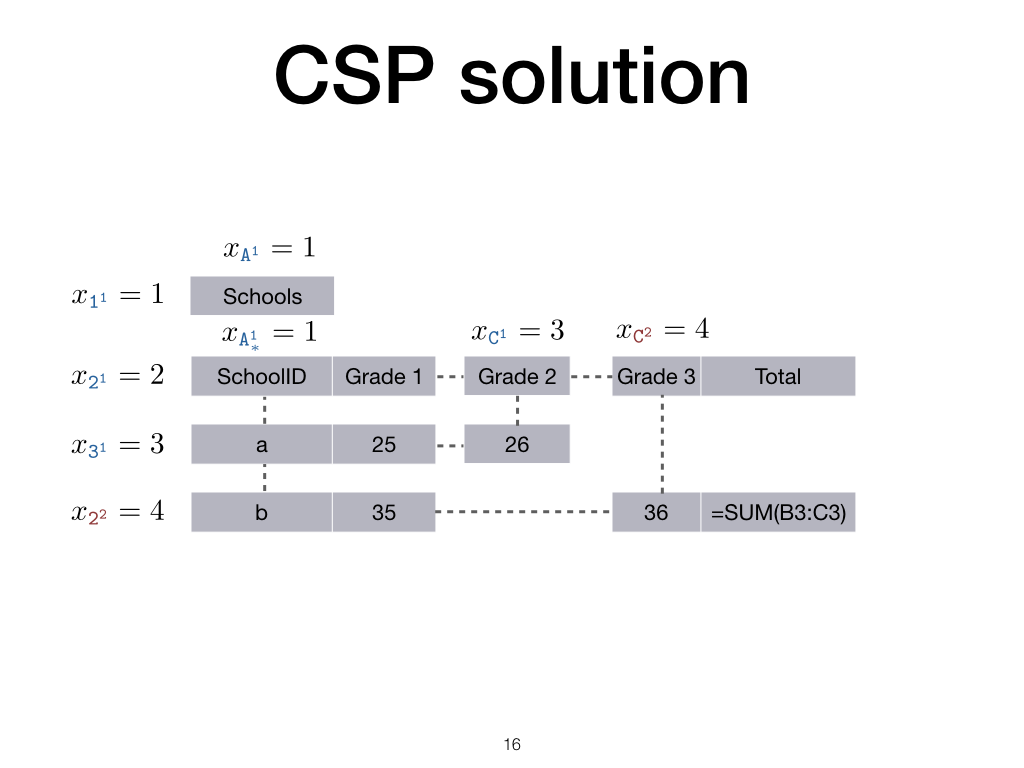

CSP solution

Each solution to the constraint satisfaction problem produces a spreadsheet.

But, the formulae are not yet correct, the user would want a formula to be repeated for new data when it makes sense, and the arguments should also take new data into account.

Formulae

So let us turn to the second part of the example, how to represent formulae.

The important observation about repeated formulae in spreadsheets is that users usually intend a formula to extend across all data that share some implicit property.

For example, here we would like the sum to be over all Grade data, in other words across all numerical data.

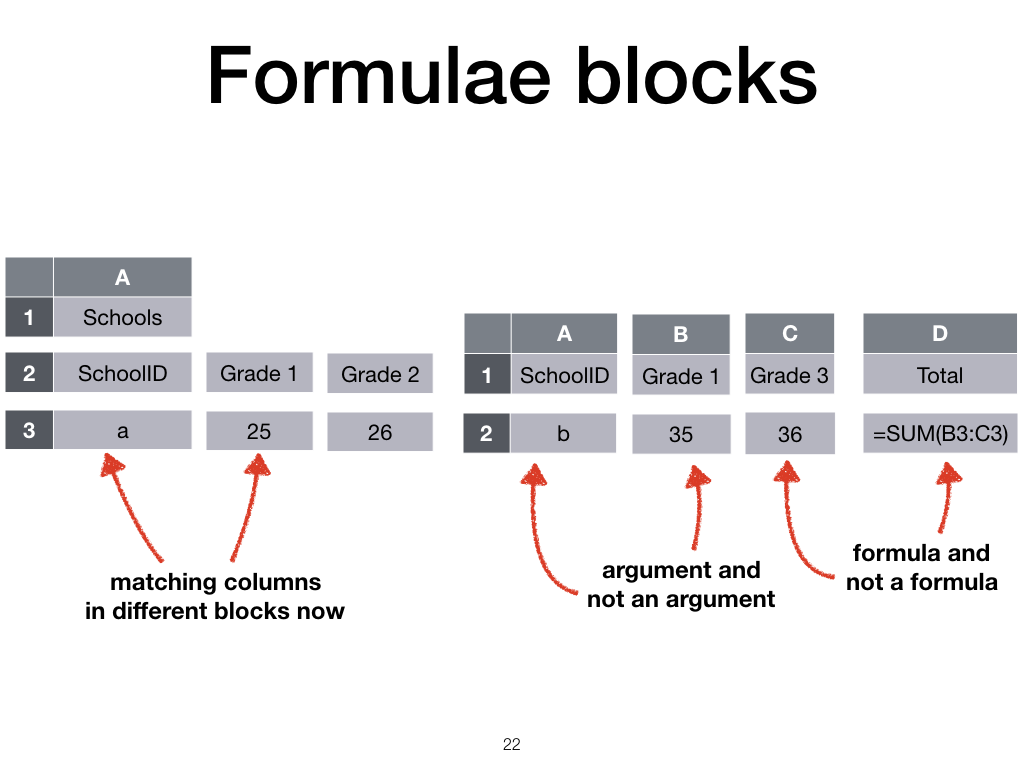

Formulae blocks

To achieve this, we have to divide our input sheets a bit differently.

We now also divide formula cells from non-formulae cells, and arguments to formulae from non-arguments.

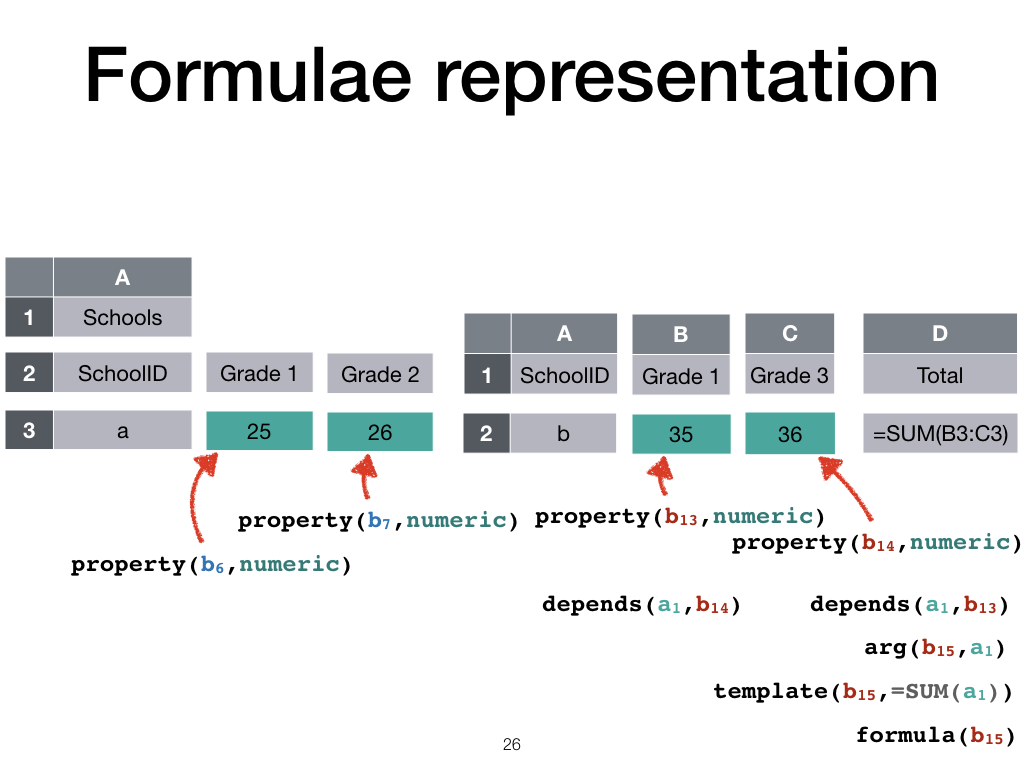

Formula representation

We then build up a knowledge base to represent the spreadsheet and the dependencies between the resulting blocks.

Formula blocks are associated with their templates and arguments, and arguments depend on other blocks.

These blocks, in turn, have certain properties. For example, all the blue blocks consists of numerical data.

Formula rules

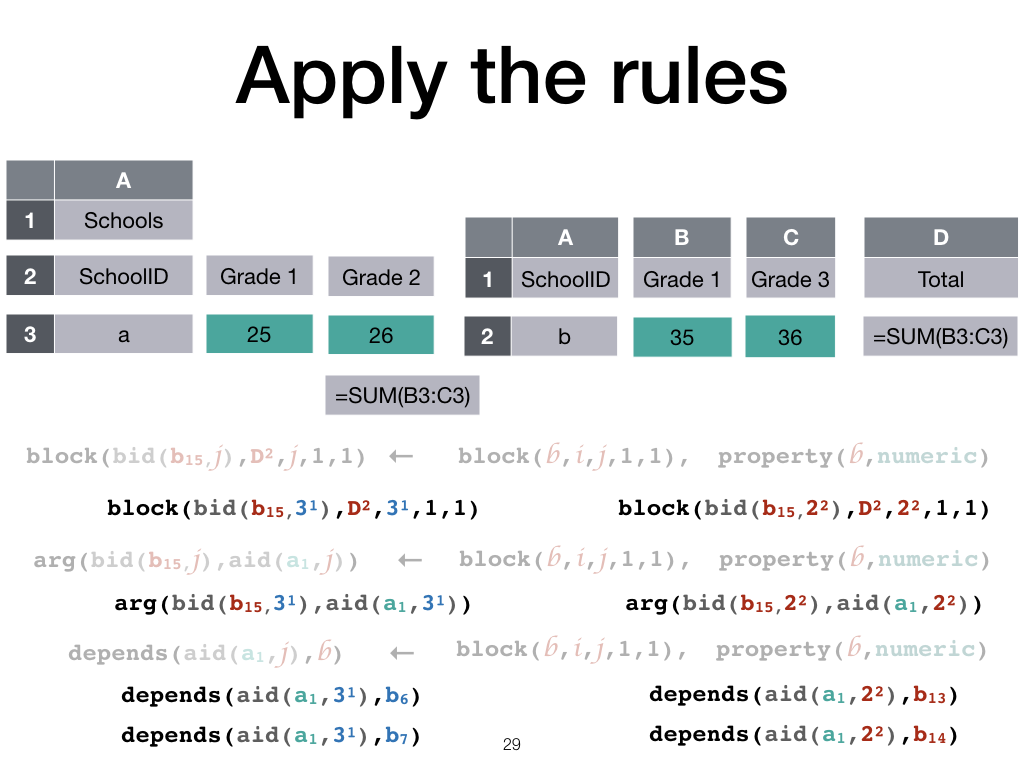

Now we can extend formulae from one spreadsheet to another.

We do this by replacing the formula block, argument, and depends predicates with rules that covers the original formula block, argument, and depends facts.

We search for rules that explain these facts in terms of argument blocks and their properties, reflecting our assumption that the user intends formulae to extend over all cells with some property.

Now if we apply these rules to both sheets, a new formula block and associated argument relations are created for the numerical data on the left-hand side.

CSP

The constraint satisfaction problem is set up as before, but now there are more blocks. The formula templates are filled in according to the dependencies of the arguments and we get the result we expect.

Experiments

That was the example. Next I will discuss some results we obtained by applying this framework in a system call splyci.

To test the system, we sampled sheets randomly from the Fuse corpus of spreadsheets and manually split them either vertically or horizontally.

We then apply the system and manually add annotations until the system is able to recover the original sheet or it becomes clear that the system cannot handle that case.

Real example

This is an example from the test set. We had to annotate the properties of some of the cells by colouring them, because there was not another unique property that the system could use to generalise the formulae using its currently implemented heuristics. See also the column match annotations, implemented as comments, since the heuristic of matching columns if their first cells match failed in this case.

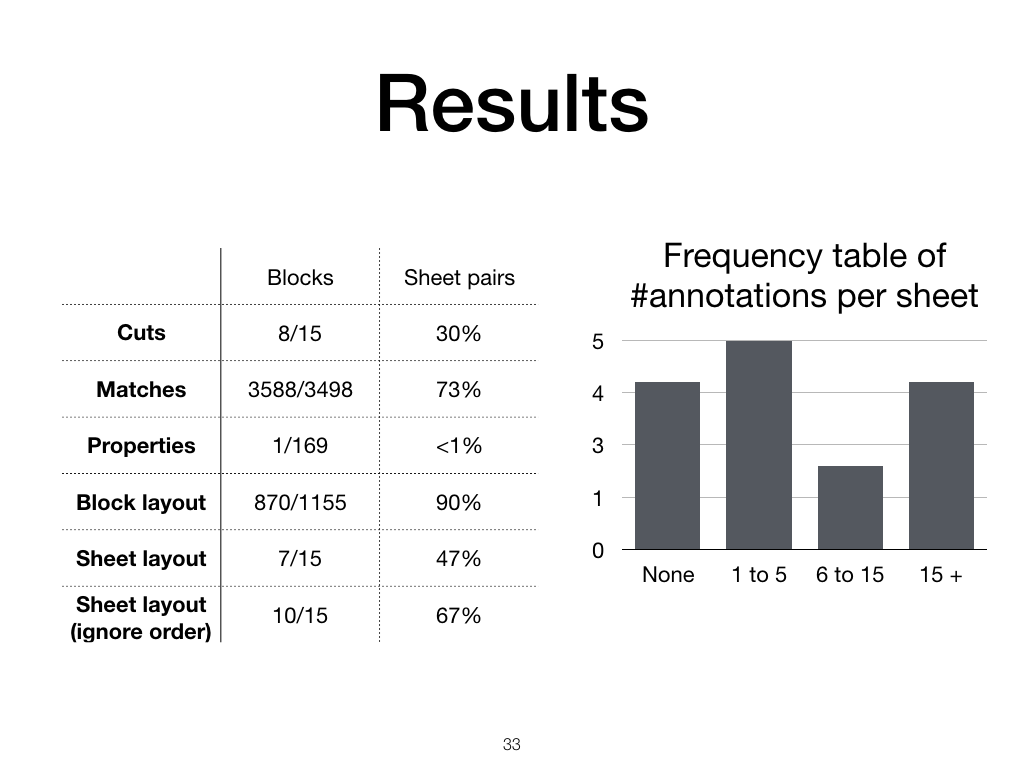

Results

The current match heuristic is more successful than the cut and property heuristics, succeeding in most of the test pairs. The block layout is mostly correct, that is, the blocks that should line up line up correctly, although the block order is only correct in about half of the sheet pairs.

When we look at the right-hand graph, we see that most sheets needed five or fewer annotations, but a few sheets needed more than 15 annotations before they could be recovered.

Future

As you can see, there is still a lot to do.

We’ve made some strong assumptions about exact column or row matches, but the framework can be extended in a natural way to allow uncertain matches.

Many of the examples were under-constrained, meaning that there were many solutions but that maybe some of them would be considered better than others by the user. It is also possible that by combining spreadsheets we get over-constrained problems without any solutions. We would like to be able to handle this case.

The validation framework should be extended with better and more test data. The amount of user effort saved by an integration system should be quantified more precisely.

And, of course, the performance can be improved by working on the sub-problems like identifying cuts, matches, and formulae rules.

Contributions

I leave you with the contributions: We presented a framework and prototypical system to integrate spreadsheets that extends formulae to the new data and lays out the result in a spreadsheet.

We did this by looking at spreadsheets as a set of user-intended layout constraints, where formulae are intended to range over all elements that share some implicit property.

We developed a system that is able to satisfactorily merge some manually split examples with fewer than 5 annotations.

For more detail check out the paper at IDA proceedings. and the code at github.com/dirko/splyci.

Collaborators

My collaborators are Steve Kroon, McElory Hoffmann, and Luc De Raedt.